I had a wonderful second-grade teacher. To this day, I can’t spell Pennsylvania without hearing the rhythmic cheer she taught us to quickly master the spelling – always ending with a big YAY!

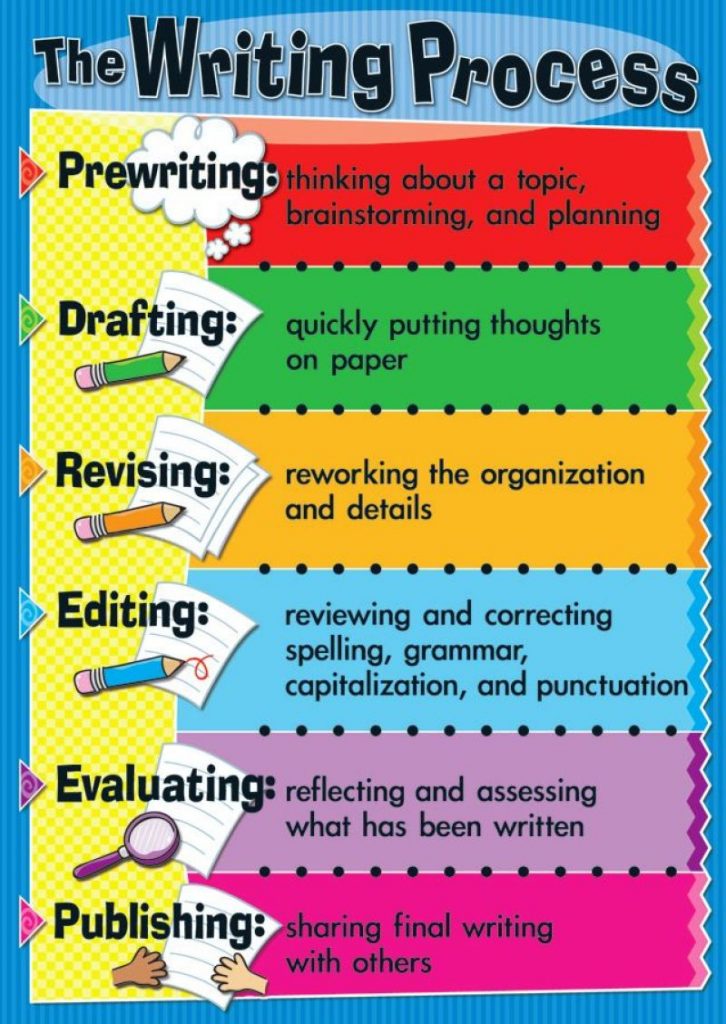

I also remember her lessons on the writing process. She drove home the separate steps of the process by reminding us that each step was a different job. When it was time to revise our work, the whole class wore decorated visors that said REVISOR across the brim.

This physical reminder helped us maintain our focus on reworking our writing instead of straying into the other steps in the process. A similar idea can help parents at their next IEP meeting.

To make the shift from parent to advocate – put on your lab coat.

Just like the writing process, the IEP process may require a parent to play different roles as the IEP is completed. At times, a parent may be singularly focused on sharing information about their child. This can include concerns for their education, their strengths, and weaknesses. At some point, the focus should shift to evaluating what the school is doing with this and other information to plan for your child’s progress.

Making this change may not come easy. It is difficult to leave the comfort of sharing information about our children that comes naturally for parents. The pressure of being something other than “just a parent” in a room full of trained educators can be difficult.

To help ease this change, an imaginary lab coat can take the place of my 2nd-grade visor. It is time to think like a scientist instead of a parent. Assuming the attributes of a scientist can help parents ask appropriate questions and evaluate the quality of a plan.

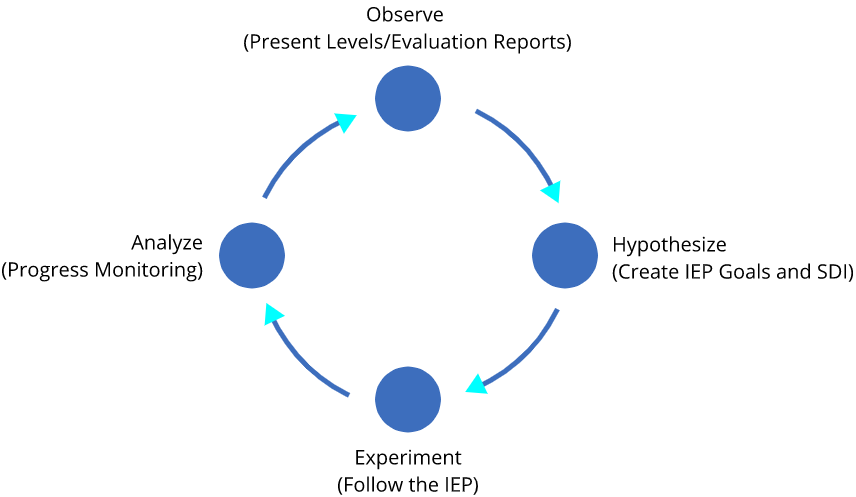

Scientists like writers use a specific process to do their work. The scientific method provides a step-by-step approach to answer questions and evaluate claims. The process values objective and observable data. It doesn’t matter what the scientist feels. Only observable data is relevant. It also requires scientists to reevaluate their position before coming to a conclusion.

The scientific method also happens to mirror the IEP process. The process begins with observations. For special education, that means completing evaluation reports or collecting present level data. Then, the IEP team uses that data to hypothesize or estimate where they hope your child will be one year from the start of the IEP. These hypotheses form our annual goals. Next, the team gets to work and follows the IEP. The success of the IEP is then monitored by conducting progress monitoring. This progress monitoring data then starts the cycle over again, with the team using the success or failure of the previous year to inform what to do during the next IEP.

Thinking like a scientist can help parents make sure this cycle is running effectively.

Would a scientist be pleased with the following example:

- Observe: Billy is bad at math.

- Hypothesis: Billy will improve his math by getting a B in math this year.

- Experiment: Billy receives regular education math instruction.

- Analyze: The progress report says Billy is making progress.

- Observe: Bill improved his math grade last year but had many opportunities to retake tests and earn extra-credit.

The answer should be no. However, many parents are so pleased to see an improved math grade, they don’t question how that grade improved. Did Billy actually improve his math skills? What math skills presented the problem to begin with? How do I know that skill isn’t going to be left behind next year?

By thinking like a scientist Billy’s IEP may read a lot differently.

- Observe: Billy is behind his peers in completing word problems. His test scores show he can correctly solve grade level addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division problems.

- Hypothesis: Given a grade level two step word problem, Billy will identify the correct operation [+ – x ÷] 85% of the time in 4 out of 5 opportunities.

- Experiment: Billy will receive direct math instruction in a learning support pull out environment.

- Analyze: The progress report contains charts depicting Billy’s progress over the year.

- Observe: Billy identified the correct operation 85% of the time in 4 out of 5 opportunities- as demonstrated by charted data of the progress monitoring attempts.

Hopefully, by putting on your imaginary lab coat and thinking like a scientist you can take a deeper look at understanding your child’s IEP.